암환자의 우울증과 카켁시아 간 시토카인 매개 연결

© 2019 by the Korean Physical Therapy Science

Abstract

Despite the advances in medical technology, there are limited therapeutic interventions for cancer. Currently, the main goal of treatment is to remove a tumor completely. However, recent studies have shown that mortality is highly influenced by symptoms such as depression and cachexia, not solely by cancer itself. Depression is caused by psychological stress, and cachexia involves extreme weight loss with skeletal muscle atrophy, which are widely observed in patients with cancer. Although those two appear completely different from each other, they have a common etiology: cytokines. The production of cytokines can lead to depression and cachexia, and it contributes greatly to the increase in mortality rate. A better understanding of depression and cachexia in patients with cancer will help establish efficient treatment strategies.

Keywords:

Cachexia, Cancer, Cytokine, DepressionⅠ. 서 론

인구 고령화로 인한 다양한 사회적 문제를 가장 먼저 겪은 나라는 일본이지만, 그 속도는 한국이 앞서고 있다. 한국은 현재 고령화 사회(aging society)를 넘어 고령사회(aged society)에 진입하였으며, 곧 초고령사회(super-aged society) 진입을 목전에 두고 있다. 이것은 단순히 일본과 한국에 국한되는 문제는 아니며, 시점의 차이는 있으나 일정 수준의 경제 규모를 가진 대부분 국가는 고령화로 인한 다양한 사회 문제에 직면하고 있다. 보건의료 측면에서 인구의 고령화는 노인성 질환의 증가로 인한 의료비용의 증가를 의미하며, 이것은 단기간이 아닌 지속적 사회 부담으로 작용한다(Arai 등, 2015). 의료기술의 발달은 일부 질환에 있어 매우 성공적인 결과를 도출하고 있으나, 암과 같은 노화 관련 퇴행성 질환은 치료적 접근이 여전히 제한적이며 노인 인구가 증가하며 계속 늘고 있는 문제를 안고 있다. 암 환자의 증가는 환자 개인의 문제를 넘어 가족과 사회의 문제로 확대된다. 암은 생명을 위협(life-threatening)하는 질환으로 환자는 암 진단과 함께 극심한 스트레스를 겪는 것이 일반적이며(Zabora 등, 2001), 이것은 우울증과 같은 정신적 문제 역시 일으키며, 독립적 활동 및 사회적 참여의 저하를 가져온다.

현재 암 치료는 대부분 암세포를 직접 사멸하거나 줄이기 위한 치료가 대부분이며, 암 발생 이후 부가적으로 나타나는 임상적 증상을 위한 치료에는 상대적으로 큰 노력이 이루어지고 있지 않다. 하지만 최근 연구에 따르면, 암 환자 중 상당수는 암이 아닌 부가적 증상으로 먼저 사망에 이른다는 것이 밝혀지고 있다. 부가적 증상 중 대표적인 것은 우울증으로, 암 환자의 대부분은 극심한 스트레스와 함께 우울감을 겪게 되며 이는 암 환자의 사망률(mortality)을 직간접으로 높이고 있는 것으로 알려져 있다. 정신적 스트레스가 질환의 진행과 사망 등 신체적 문제와 연결된 것이다. 암 환자에게서 나타나는 우울증은 건강한 일반인이 겪는 우울증과 구별되며, 다른 만성적 질환 환자에게서 관찰되는 우울증과도 다른 특성을 보인다. 암 환자는 정신적, 심리적 특성 외에 고유한 근 생리학적 특성 또한 갖는다. 많은 경우 빠른 체중 감소를 겪으며, 특히 골격근의 급격한 감소가 관찰된다. 이것은 별도로 암카켁시아(cancer cachexia)로 불리며, 카켁시아는 암으로 인한 사망의 최소 20% 정도에서 직접적 원인으로 추정된다(Fearon 등, 2012). 암 종류에 따라 편차가 있지만, 위암(gastric cancer), 이자암(pancreatic cancer) 환자의 경우 약 80%에서 카켁시아의 영향을 받는 것으로 알려져 있다(Laviano 등, 2005). 카켁시아는 부족한 영양분의 섭취로 인한 근육 손실을 의미하는 기아(starvation)와는 구별되어 사용되며, 전통적인 영양 공급만으로는 개선되지 않는 것이 특징이다. 또한, 노화와 함께 자연적으로 발생하는 근육감소증(sarcopenia)과도 구별된다(Thomas, 2002). 정신적 변화와 근 생리학적 변화는 일면 관련이 없어 보이나, 그 원인을 들여다보면 공통적 원인 요소(common etiology)가 관찰된다. 염증 시토카인(inflammatory cytokine) 수치 증가 시 우울과 카켁시아 증상이 동물과 인간 모두에서 관찰되고 있으며, 두 가지 증상이 동반하는 경우가 다수이다. 또한, 둘 다 암 환자의 사망률을 높이는 주요 인자로 현재 규명되고 있다.

본 종설에서는 시토카인이 인체에 미치는 역할을 바탕으로, 두 중요한 임상적 증후의 연관성을 고찰하고자 한다. 이는 암 환자의 생존기간(survival time), 생존율(survival rate)과 매우 밀접한 관계에 있으며, 건강증진 외 삶의 질 개선에서도 매우 중요한 부분으로 고려될 수 있다.

Ⅱ. 스트레스와 시토카인

암 환자의 심리적 특성과 생리적 특성의 연결은 정신신경면역학(psychoneuroimmunology)을 통해 탐구되고 있다. 많은 환자는 암 ‘진단 후’, ‘치료 중’, ‘치료완료 후 추적 관찰’ 기간 동안 불안(anxiety) 또는 우울과 같은 심리적 고통(psychological distress)을 겪는다(Zabora 등, 2001). 또한, 다른 질환의 환자보다 높은 불확실성(uncertainty)과 비관주의(pessimism)적 특성을 갖는다(Mishel 등, 1984).

심리적, 정신적 스트레스는 전-염증 경로(pro-in-flammatory pathway)를 활성화하며, 인터루킨(Interleukin; IL)-6, 종양괴사인자(tumor necrosis factor; TNF)-α 와 같은 시토카인(cytokine)의 증가를 초래하며 이를 통해 연쇄적 생리 변화를 만들어 낸다(Zabora 등, 2001). 구체적으로는 스트레스에 의해 활성화되는 주요한 신경학적 경로인 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 축(hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis)과 교감신경계(sympathetic nervous system)를 자극한다(Black, 1994; Chrousos, 1995). 일반적으로 우울감이 있는 환자는 활성화된 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 축과 증가된 크로티솔(cortisol) 수치를 보이며, 이때 전-염증 시토카인의 분비가 자극된다. 시토카인은 다시 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 축과 코르티솔의 생산을 자극한다 (Irwin과 Miller, 2007). 신경정신장애(neuropsychiatric disorder)에서는 비정상적 글루코코르티코이드(glucocorticoid) 신호가 나타나는데, 이것은 암 환자에게서도 유사하게 관찰된다. 스트레스로 인한 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 축의 지속적인 활성화는 면역 체계를 손상시키고, 이것은 질환의 진행 속도에 악영향을 미칠 수 있다. 또한, 코르티솔 수용체(cortisol receptor)가 정상적으로 작동하지 않아 코르티솔 저항(cortisol resistance)을 유발하며, 손상된 되먹임(feedback)은 지속해서 면역 세포의 활성화를 촉진한다(Pace 등, 2007). 이때 면역 세포의 활성화는 다시 시토카인의 증가를 유도하는 악순환에 놓이게 된다.

사실 시토카인은 큰포식세포(macrophage)와 림프구(lymphocyte)에 의해 방출되는 가용성 매개물질(soluble mediator)로 면역 체계에서 긍정적 측면과 부정적 측면을 동시에 갖는다. 시토카인의 생성은 T도움세포(T helper cell)의 기능적 활동에 따라 크게 두가지로 분류된다. 먼저, 유형 1 T도움세포(type 1 helper cell)는 세포독성 림프구(cytotoxic lymphocyte), 자연살해세포(natural killer cell), 큰포식세포의 활성화를 통해 세포 면역 반응을 중재하며, 인터페론(interferon; IFN)-γ, TNF-α, IL-2과 같은 시토카인의 생산에 참여한다. 초기 선천면역(innate immune) 반응에서 생성되는 시토카인 중 IL-12는 주요 세포로 조절되는 면역 유도인자(inducer)이기도 하다. 그리고 유형 2 T도움세포(type 2 helper cell)는 항체(antibody)에 의해 면역 반응을 강화하며, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10과 같은 시토카인의 생산에 참여한다. 유형 1 T도움세포와 유형 2 T도움세포는 상호 억제 작용을 한다. 예를 들어, 유형 2 T도움세포에 의해 방출되는 IL-4와 IL-10은 유형 1 T도움세포의 활동을 억제하며, 체액성 면역 반응(humoral immune responses)을 자극한다(Kim과 Maes, 2003).

시토카인은 스트레스의 노출 지속 정도에 따라 다른 기전 특성을 갖는다. 급성 심리적 스트레스(psychological stress)는 전-염증 시토카인을 증가시키는 것은 물론, 유형 1 T도움세포를 통해서도 시토카인의 증가를 유도한다. 반면 만성 심리적 스트레스는 조금 더 복잡한 형태로 반응한다. 만성 스트레스 노출시 유형 1과 유형 2 T도움세포 사이의 균형이 깨지며 유형 2 T도움세포에 의한 반응이 전반적으로 커지며, 이에 관련된 전-염증 시토카인의 증가가 발생한다. 스트레스로 인하여 유발되는 시토카인은 인돌아민2,3-이산소화효소(indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase)의 활동을 자극하고, 우울증과 같은 세로토닌 결핍 장애(serotonin depletion-related disorders)를 유발할 수 있다. 또한, 심리적 스트레스로 생산된 시토카인은 심혈관질환 및 자가면역 질환의 위험성을 증가시키고, 뇌의신경퇴행성 변화(neurodegenerative change)에 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 심리적 스트레스에 반복적 노출 시 뒤이은 스트레스 상황에서 염증 반응이 더욱 민감하게 나타나기도 한다(Glaser과 Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). 또한, 면역 체계에 관여하는 다양한 세포와 분자 수준에서의 인자들은 지속적 스트레스 노출 시 정상적 기능이 상실되거나 손상된다.

Ⅲ. 시토카인이 우울증과 카켁시아에 미치는 영향

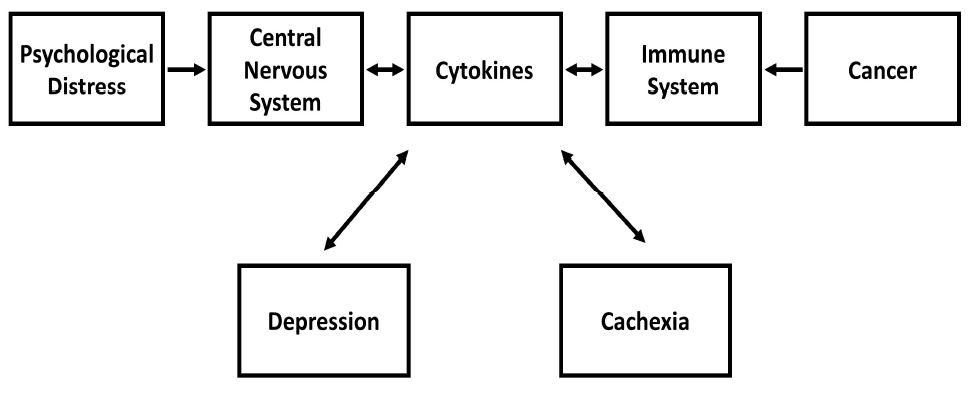

암 환자에게서 관찰되는 심리적 문제와 근 생리학적 문제는 서로 다른 특성으로 분리되어 생각될 수 있다. 하지만 둘은 서로 다른 특성에도 불구하고, 함께 고민되어야 할지 모른다. 우울증과 카켁시아의 발생을 들여다보면 공통 병인(common etiology)이 관찰되며 그 영향력이 매우 크다(그림 1). 증가한 전-염증 시토카인은 신체적, 심리적 스트레스인자(physical and psychological stressor)의 수치를 높인다(Kiecolt-Glaser과 Glaser, 2002).

1. 우울증

암 환자는 다른 일반적 질환을 가진 환자보다 높은 스트레스를 받는 것으로 알려져 있다. 낮은 치료 효과 및 생존율, 높은 치료 비용, 빠른 질환의 진행 등이 극심한 불안과 함께 심리적 스트레스를 일으키고 이는 우울증으로 연결될 수 있다<표 1>. 실제 암 환자의 우울증 유병률(prevalence rate)은 일반인과의 비교뿐만 아니라 암을 제외한 다른 질환과의 비교에서도 높다(Linden 등, 2012). 암 환자의 우울증은 생물학적, 사회심리학적 요소가 복합적으로 작용하여 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 먼저 생물학적 특성은 염증과 깊은 관련을 보인다. 많은 연구 결과 염증 반응은 우울증의 병태생리학적 측면에서 매우 중요한 역할을 한다는 것이 밝혀졌다.

스트레스는 교감신경계(sympathetic nervous system)와 부교감신경계(parasympathetic nervous system) 경로를 통해 생리적 염증 반응을 촉진한다(Raison과 Miller, 2003). 실제 같은 암 환자 중에서도 우울증을 겪고 있는 암 환자는 그렇지 않은 환자에 비해 유의하게 높은 수치의 IL-6가 관찰된다(Musselman 등, 2001; Soygur 등, 2007). 전-염증 경로를 표적으로 하는 치료가 임상에서 고민되는 이유이다. 또한, 수술로 인한 조직 손상, 화학 요법(chemotherapy), 방사선치료(radiotherapy)와 같은 항암 치료로 사용되는 다양한 중재들은 핵인자 카파 B(nuclear factor kap-pa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NF-κB)의 전사인자(transcription factor)의 발현을 유발하고, 또한 IL-1, IL-6, INF-γ; TNF-α와 같은 시토카인의 생성을 촉진한다(Bianchi, 2007). TNF-α와 IL-1의 증가는 세로토닌과 노르아드레날린(noradrenaline)의 재흡수 운송자(reuptake transporter)의 발현과 활동을 증가시키며, 이는 5-하이드록시트립타민(5-hydroxytryptamine)와 노르아드레날린의 시냅스 농도(synaptic concentration)를 낮추고, 우울 행동(depressive behavior)을 초래할 수 있다(Zhu 등, 2005; Raison 등, 2006). 시토카인은 코르티코트로핀분비호르몬(corticotropin-releasing hormone; CRH)의 분비를 증가시키고, CRH는 우울증에서 관찰되는 행동적 변화를 일으키기도 한다(Holsboer과 Ising, 2008). 그밖에 시토카인은 신경발생(neurogenesis)의 주요 역할을 담당하는 뇌유래신경영 양인자(brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BDNF)와 같은 신경성장인자(neural growth factors)의 수치를 낮춘다. BDNF와 신경성장인자의 낮은 수치는 우울증의 발병과 깊은 연관이 있다(Duman과 Monteggia, 2006). 우울증을 가진 경우 전반적으로 시토카인의 수치가 높게 나타나며, 시토카인은 신경내분비 기능(neuroendocrine function), 시냅스 형성성(synaptic plasticity), 행동 스트레스(behavior stress)처럼 우울증과 관련된 다른 여러 인자와 넓게 상호작용하게 된다. 생물학적 측면 외 사회심리학적 측면에서 보면 우울증은 극단적 불확실성에서 비롯된다. 우울증은 비 병리학적 단순 슬픔부터 임상적 진단을 거친 우울증까지 다양하게 분류된다. 정상적 환경에서 인간은 자체적으로 일정 수준의 정신적 고통과 스트레스를 조절하여 지속적 우울감 또는 절망감과 같은 질환 수준의 무기력함에 빠지는 것을 경계할 수 있는 능력을 갖추고 있다. 하지만 조절가능한 수준을 넘어서는 스트레스에 지속적 노출 시 임상적으로 진단 가능한 심각한 우울증이 발생하며, 이 경우 단순한 휴식은 큰 도움이 되지 않기에 적절한 치료적 중재가 제공되어야 한다.

2. 카켁시아

염증은 양날의 검(double-edged sword)과 같다. 유해물질 및 암세포를 제거하기 위한 긍정적 역할 수행은 물론, 때로는 암세포의 성장을 돕는 부정적 역할도 수행한다. 초기에 발생하는 염증 반응은 주로 긍정적 측면을 많이 갖고 있으나, 만성으로 이어지면 많은 부정적 문제를 발생시킨다. 만성 염증은 단순히 1차 염증발생 부위에 국한하지 않고 골격근, 지방, 뇌, 간 등 신체 여러 부위에 포괄적으로 영향을 미친다. 특히, TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IFN-γ와 같은 전-염증 시토카인은 병리적 근 손실로 알려진 골격근의 카켁시아 발생을 유도하며, 이중 TNF-α는 카켁시아에 있어 가장 특징적 역할을 수행한다(Mantovani 등, 2000). 식욕부진(anorexia)을 유발하는 것은 물론이고, NF-κB의 경로를 통해 골격근의 위축(atrophy)을 지속해서 유도한다. TNF-α와 같은 시토카인의 분비는 단백질분해 경로(proteolytic pathway)와 관련된 세포 단위의 변화를 일으켜 보다 빠른 단백질분해(proteolysis)를 일으킨다(Bossola 등, 2001; Busquets 등, 2003). 또한, IFN-γ와 IL-1의 활동을 도와 근육 소모를 촉진한다. TNF-α 차단(blockade) 연구에서는 카켁시아로 인한 피로의 감소가 일부 관찰되었으나 그 외 다른 효과는 제한적이었다(Monk 등, 2006). 단백질 분해 및 소실은 매우 복잡한 기전과 단계로 이루어져 있어 TNF-α에 특정화된 치료만으로는 효과가 제한적일 수 있다. 이 때문에 TNF-α 외 IL에 관한 연구도 활발히 진행 중이다. IL-6은 동물연구에서 단독적으로 카켁시아의 진행을 촉진하는 것이 관찰되었다(Baltgalvis 등, 2008). IL-6 수치는 카켁시아 진행 정도와 높은 상관관계를 보이며, 특히 전립샘암 환자(prostate cancer)에서 예후가 매우 좋지 않았다(Kuroda 등, 2007). Il-6는 시토카인을 포함하는 면역 체계에 의해서도 생성되지만, 종양으로부터 직접 생성되는 특징을 갖는다(Zaki 등, 2004). 암 환자를 대상으로 한 연구에서 증가한 시토카인의 수치는 상호 간에 유기적으로 연결되어 종합적으로 카켁시아를 증진 시키는 것으로 나타났다(Mantovani 등, 2000). 시토카인 중 염증을 유발하는 물질의 발현 증가는 염증 수치를 낮추는 IL-4, IL-10, IL-12과 같은 시토카인의 발현은 거꾸로 감소시킨다(Argilés 등, 2011). 반대로 과도한 염증 반응의 억제 시 카켁시아 진행에 일부 긍정적 효과가 있는 것으로 보고되고 있다(Lundholm 등, 1994; Fearon 등, 2013).

카켁시아 발생 시 환자는 단, 기간에 급격한 골격근의 소실을 겪는다. 일반적으로 최근 6개월 동안 5% 이상의 체중 감소가 있거나, BMI 지수가 20 미만이며 체중 감소는 2% 이상일 경우 카켁시아로 의심할 수 있다. 카켁시아에서의 체중 감소는 골격근의 소실에만 기인하지 않는다. 근육을 형성하는 단백질뿐만 아니라 지방과 탄수화물에서도 비정상적 대사가 동반되어 발생한다. 더불어 기초 대사량(basal metabolic rate)과 전체 에너지 대사(total energy expenditure)가 증가한다. 피로와 쇠약(weakness)으로 심각한 움직임 제한이 발생하기도 한다(Cohen 등, 2015). 식욕부진이 동반하여 나타나기도 하지만, 영양 섭취의 부족 또는 불균형이 카켁시아의 직접적 원인이 아니므로, 일반적 식이요법만으로는 카켁시아에서 나타나는 근 손실을 막을 수 없다. 카켁시아는 다양한 암 종류에서 관찰되지만, 폐암 또는 췌장암에서는 그 영향 정도가 크며 예후 역시 매우 좋지 않다. 카켁시아로 인한 체중 소실이 있는 환자는 그렇지 않은 환자에 비해 유의하게 낮은 생존율을 보인다(Tisdale, 1997).

3. 사망 예측 요인으로서의 우울증과 카켁시아

우울증은 심리적 요소로 신체에 대한 영향력은 한정적이라는 견해가 많았다. 하지만 많은 연구 결과를 바탕으로 현재 그 영향성과 중요성은 몇몇 부분에서 받아들여지고 있다. 먼저 우울증과 질환 진행 정도와의 연관성이다. 우울증의 정도는 질환의 정도를 일정부분 반영한다는 연구가 있으며(Spiegel과 Giese-Davis, 2003), 심리 요소들이 초기 암 진행상태에서 질환의 진행과 사망률에 매우 강한 영향을 미친다는 연구도 있다(Cwikel 등, 1997). 물론 암이 상당 부분 진행된 경우에도 사망률과 연관성이 관찰되고 있지만, 초기 단계에 영향이 더 크다고 할 수 있다(Pinquart와 Duberstein, 2010). 구체적으로는 2년 이하의 기간에서 매우 높은 상관관계를 보인다. 암 진행 시 생존기간이 증가함에 따라 다른 부가적인 요소들이 복합적으로 작용하는 것으로 생각된다. 두 번째로, 우울증은 암종류에 따라 우울증의 연관 정도가 더 클 수 있다. 예를 들어 백혈병(leukemia), 림프종(lymphoma), 유방암, 폐암, 뇌종양의 경우 환자의 생존 기간에 영향을 상대적으로 크게 미치는 것으로 나타난다. 마지막으로, 나이에 따른 반응이 상이하다. 초기 연구에서는 젊은 환자에게서 노인과의 비교에 있어 더욱 강한 연관 관계가 보고되었지만, 최근 확장된 메타 분석에서는 고령의 환자에게서 더 높은 상관성을 보인다(Pinquart와 Duberstein, 2010). 고령 환자의 경우 우울증에 대한 적절한 치료가 이루어지지 않을 수 있고, 치료에 대한 동기부여가 강하지 않기 때문에 더욱 큰 문제가 될 수 있다. 신체적으로는 체력이 낮고 쇠약하여 항우울 치료에 대한 부작용을 견디기 어려울 수도 있다. 우울증이 사망률을 증가시키는 것은 다음과 같은 세 가지로 설명되고 있다(Spiegel과 Giese-Davis, 2003). 첫째, 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 축의 조절장애(dysregulation), 신경내분비기능 및 면역기능 장애와 같이 사망률을 높일 수 있는 요소에 우울증이 상당 부분 영향을 미친다. 둘째, 우울증이 있는 환자는 건강 유지를 위한 예방적 검진 및 주기적 방문 치료를 유지하지 않을 가능성이 크다(DiMatteo 등, 2000). 이에 더해 규칙적 운동을 수행할 가능성은 적었지만, 음주 및 흡연에 노출된 확률은 높다(Wulsin 등, 1999). 셋째, 암으로 인해 발생하는 많은 증상과 치료 중 발생하는 부작용(side effect)은 우울증 환자에게서 발견되는 증상과 유사하다. 즉, 우울 증상은 질환의 정도를 일부 간접적으로 나타낸다. 우울 증상은 진행된 암에서 더욱 흔하게 발생한다(Massie, 1998). 이처럼 우울증은 사망률에 높은 영향을 미치는 중요한 요소임에도 불구하고, 여전히 의료기관에서는 우울증 검사를 하지 않거나 정밀하게 확인하지 않는 경우가 많다(Dalton 등, 2008). 이 때문에 임상에서 실제 우울증을 앓는 환자는 보고되고 있는 비율보다 높을 것으로 추정된다.

우울감과 함께 근육 질량(muscle mass)은 시토카인에 크게 영향을 받는다. 골격근은 독립적 기관으로 분류되며 몸에서 가장 큰 기관으로 여겨지고 있다. 인슐린과 같은 호르몬의 분비부터 대사와 염증 같은 생물학적 과정에까지 참여한다. 그러므로 근 손실은 단순히 기능적 움직임의 제한에 그치지 않고 환자의 생존기간에도 큰 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 일반적으로 비만은 건강 유지에 있어 위험 요소로 간주하지만, 암 환자는 과체중보다 저체중이 오히려 위험할 수 있다(Schlesinger 등, 2014). 유방암 환자의 연구에서 근 손실 시 높은 사망률 외에 화학요법으로 인한 부작용이 더 쉽게 발생하는 것으로 나타났다(Shachar 등, 2017). 유방암 환자 3241명을 대상으로 한 연구에서는 낮은 근육 질량을 가진 약 1/3 환자군은 적절한 근육량을 유지하고 있는 환자군에 비해 사망 위험성이 상대적으로 높았다(Caan 등, 2018). 유방암 외 결장암(colorectal cancer)에서도 이와 유사하게 근 감소가 진단된 환자의 경우 낮은 생존율을 보였다(Caan 등, 2017). 많은 연구에서 낮은 근육량을 가진 환자의 경우 예후가 상대적으로 좋지 않은 것은 물론이고 생존율이 짧을 수 있음이 입증되었다. 특히, 90세 이상 고령 환자에서는 근 손실이 사망률을 크게 높인다(Wang 등, 2019). 고령 환자의 경우 카켁시아는 근육감소증과 구별되어 고려되어야 한다. 노화와 함께 발생하는 근 손실은 자연스러운 현상으로 카켁시아와는 성격이 다르다. 암 환자에게서 관찰되는 카켁시아의 경우 근육을 생성하는 단백질 합성은 제한하고 근육의 소실을 유발하는 단백질 분해는 빠르게 작동한다. 이로 인하여 일반적 노화보다 많은 근 손실을 유발하며 환자의 건강에 치명적 영향을 미친다. 근 손실은 전산화단층촬영술(Computed tomography scan)을 통해 쉽게 측정할 수 있지만, 신체비만지수(body mass index) 역시 충분한 임상적 가치를 지닌다. 신체비만지수는 측정이 간단하고 빠르며, 높은 비용을 요구하지 않기 때문에 임상에서 부담 없이 적용 및 참고할 수 있다.

4. 치료적 중재 및 의학적 효과

최근 메타분석을 보면 일정 수준의 우울증은 사망률을 39%까지 증가시키며, 적은 우울감조차 사망 위험성을 25% 증가시키는 것으로 나왔다(Pinquart와 Duberstein, 2010). 심리치료(Psychological therapy) 및 정신사회지지(psychosocial support) 시 불안과 우울, 통증의 감소는 물론이고, 대처능력의 개선을 볼 수 있다(Spiegel 등, 1981). 또한 항우울제(antidepressant)는 IL-10 과 같은 항염증(anti-inflammatory) 물질의 생산을 증가시키고, 비정상적 시토카인의 생산을 일정 부분 정상화할 수 있다 (Kenis와 Maes, 2002). 심리적 치료가 질환을 낫게 하는 직접적 치료의 효과는 불명확한 부분이 존재하지만, 적어도 질환의 진행을 다소 늦추는 것과 생존기간의 증가 측면에서는 그 효과를 인정받고 있다. 다양한 연구에서 우울증 치료 후 생존기간의 증가가 관찰되었다(Richardson 등, 1990; Kuchler 등, 1999; McCorkle 등, 2000). 치료는 집중적이고 지속적인 중재가 아닌 간단한 방문치료만으로도 효과가 있었다(McCorkle 등, 2000). 암 환자에게 언제까지 정신사회적 지지와 치료가 필요한지에 대해서는 명확하지 않다 하지만 . 일반적 권고는 사망 전까지 지속적 치료를 제공하는 것을 제안한다. 치료 제공 시 기간과 함께 치료 시기, 치료 형태 등이 함께 고민되어야 한다.

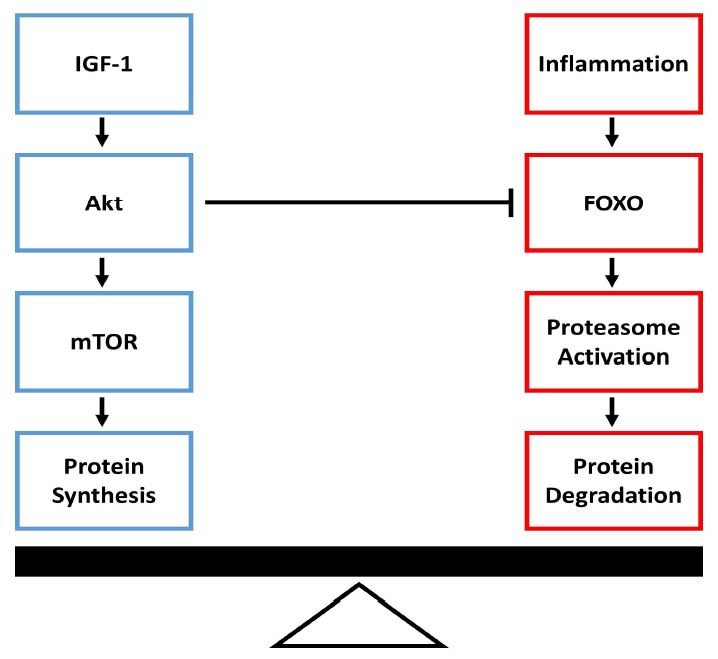

카켁시아의 경우 단순 영양 보충보다는 운동과 결합 시 보다 효과적인 결과가 도출되는 것으로 알려져 있다. 특히 저항 운동 시 마른체중(lean body mass)과 근력(muscle strength)은 증가하고, 염증표지자(inflammatory marker)와 피로는 감소하는 것으로 나타났다(Little과 Phillips, 2009). 근육 단백질의 소실은 단백질 분해와 합성 능력이 균형을 이루지 못하고, 순결과(net result)가 분해 쪽으로 기우는 경우 발생한다 (그림 2). 카켁시아는 앞서 언급한 바와 같이 단순히 영양부족으로 인한 문제는 아니며, 시토카인으로 인해 유발되는 만성적 염증반응이 주요하므로 최근에는 염증시토카인을 표적화한 항염증제(anti-inflammatory agent)에 관한 연구가 활발하다(Reid 등, 2012). 먼저 대중적으로 널리 사용되는 비스테로이드소염제(nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)의 경우 IL-6의 수치를 일정 부분 낮추며, 근육 합성에 중요한 단백질 대사를 일정 부분 개선해줄 수 있다 (McMillan 등, 1995). 면역조절물질약(immunomodulatory drug)인 탈리도미드(thalidomide)에 대한 시도에서는 효과적으로 TNF-α를 억제하는 것이 발견되었다. 후천성 면역 결핍 증후군(acquired immune deficiency syndrome) 환자를 대상으로 한 치료에서는 유의한 삶의 질 향상이 보고되었으며 (Klausner 등, 1996), 일부 연구에서는 식욕증진에서도 효과가 증명되었다(Bruera 등, 1999). 동물실험에서는 인위적 TNF-α 또는 IL-1 투여 시 암 환자의 카켁시아에서 관찰되는 유사한 근 손실이 발생하였으며(Fong 등, 1989), 반대로 TNF-α 유형 I 수용체(type I receptor) 투여 시 유의한 음식 섭취 증가와 체중 증가가 관찰되기도 하였다(Torelli 등, 1999). 하지만, 우울증과 유사하게 염증 물질의 복잡한 반응 기전 때문에, 카켁시아도 항시토카인 면역글로불린 접근만으로는 한계가 있었다(Costelli 등, 1993). 유의한 효과를 위해서는 단일 접근이 아닌, 다양한 시토카인과 함께 카켁시아에 영향을 미치는 다른 매개체를 종합적으로 고려해야 할 것이다(Argilés와 López-Soriano, 1999). 앞으로 이와 관련 많은 추가 연구가 필요하다.

Ⅳ. 결론

과거에는 환자에게서 관찰되는 우울증은 매우 정상적 심리 반응으로, 치료 대상으로 인식되지 않았다(Newport와 Nemeroff, 1998). 하지만 건강한 일반인이 겪는 우울증과 암 환자와 같은 만성적 환자에게서 발생하는 우울증은 그 특성과 영향 정도가 다르기에 명확히 구별되어야 한다. 우울증을 겪고 있는 암 환자의 2/3는 일정한 수준 이상의 불안을 표현한다(Linden 등, 2012). 이는 비활동성 생활양식(sedentary lifestyle)을 만들 것이고, 시토카인의 생산을 증가시킬 수 있다. 증가한 시토카인은 다시 우울증과 관련된 증상의 악화를 야기하는 악순환적 구조에 놓일 수 있다(Flynn과 McFarlin, 2006). 조기에 개입하여 정확한 측정과 함께 주기적 확인이 필요하며, 진단 시 적절한 치료가 병행되어야 한다. 우울증과 유사하게 암 환자의 체중 감소 역시 식욕부진과 영양 부족으로 치부되어 적극적 치료 대상으로 간주하지 않는 경향이 있다. 하지만, 이 역시 질환의 정도와 생존기간에 큰 영향을 미치는 요소임이 증명되고 있다. 우울증과 카켁시아는 시토카인의 분비와 상당히 밀접한 관계에 놓여있다. 질환을 일으키는 원인 물질에 대한 직접적 치료가 물론 중요하지만, 때로는 이차적인 증후가 더욱 심각한 문제를 일의 킬 수 있다. 치료적 효과와 생존기간을 높이기 위해서는 함께 고려되고 치료되어야 할 것이다. 암 환자의 경우 우울증과 카켁시아에 대한 보다 깊은 이해가 새로운 임상적 견해와 치료전략 수립에 도움을 줄 것이다.

Acknowledgments

이 연구는 2019년도 우송대학교 교내학술연구조성비 지원을 받음.

References

-

Aass N, Fosså SD, Dahl AA, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer patients seen at the Norwegian Radium Hospital. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(10):1597–1604.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00054-3]

-

Arai H, Ouchi Y, Toba K, et al. Japan as the front-runner of super-aged societies: Perspectives from medicine and medical care in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(6):673–687.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12450]

-

Argilés JM, Busquets S, López-Soriano FJ. Anti-inflammatory therapies in cancer cachexia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;668 Suppl 1:S81-86.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.07.007]

-

Argilés JM, López-Soriano FJ. The role of cytokines in cancer cachexia. Med Res Rev. 1999;19(3):223–248.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(199905)19:3<223::AID-MED3>3.0.CO;2-N]

-

Baltgalvis KA, Berger FG, Pena MMO, et al. Interleukin-6 and cachexia in ApcMin/+ mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(2):R393-401.

[https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00716.2007]

-

Berard RM, Boermeester F, Viljoen G. Depressive disorders in an out-patient oncology setting: prevalence, assessment, and management. Psychooncology. 1998;7(2):112–120.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199803/04)7:2<112::AID-PON300>3.0.CO;2-W]

-

Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(1): 1–5.

[https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0306164]

-

Black PH. Central nervous system-immune system interactions: psychoneuroendocrinology of stress and its immune consequences. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38(1):1–6.

[https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.38.1.1]

-

Bodurka-Bevers D, Basen-Engquist K, Carmack CL, et al. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78(3 Pt 1):302–308.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2000.5908]

-

Bossola M, Muscaritoli M, Costelli P, et al. Increased muscle ubiquitin mRNA levels in gastric cancer patients. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280(5):R1518-1523.

[https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.5.R1518]

-

Bruera E, Neumann CM, Pituskin E, et al. Thalidomide in patients with cachexia due to terminal cancer: preliminary report. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(7):857–859.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008329821941]

-

Buccheri G. Depressive reactions to lung cancer are common and often followed by a poor outcome. Eur Respir J. 1998;11(1):173–178.

[https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.98.11010173]

-

Busquets S, Aranda X, Ribas-Carbó M, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha uncouples respiration in isolated rat mitochondria. Cytokine. 2003;22(1–2):1–4.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-4666(03)00098-X]

-

Caan BJ, Meyerhardt JA, Kroenke CH, et al. Explaining the Obesity Paradox: The Association between Body Composition and Colorectal Cancer Survival (C-SCANS Study). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):1008–1015.

[https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0200]

-

Caan BJ, Cespedes Feliciano EM, Prado CM, et al. Association of Muscle and Adiposity Measured by Computed Tomography With Survival in Patients With Nonmetastatic Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(6):798–804.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0137]

-

Carroll BT, Kathol RG, Noyes R, et al. Screening for depression and anxiety in cancer patients using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15(2):69–74.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(93)90099-A]

-

Chen ML, Chang HK, Yeh CH. Anxiety and depression in Taiwanese cancer patients with and without pain. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):944–951.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01560.x]

-

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. ‘Are you depressed?’ Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(5):674–676.

[https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.5.674]

-

Chrousos GP. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1351–1362.

[https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199505183322008]

-

Ciaramella A, Poli P. Assessment of depression among cancer patients: the role of pain, cancer type and treatment. Psychooncology. 2001;10(2):156–165.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.505]

-

Cohen S, Nathan JA, Goldberg AL. Muscle wasting in disease: molecular mechanisms and promising therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(1):58–74.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4467]

-

Colón EA, Callies AL, Popkin MK, et al. Depressed mood and other variables related to bone marrow transplantation survival in acute leukemia. Psychosomatics. 1991;32(4):420–425.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(91)72045-8]

-

Costelli P, Carbó N, Tessitore L, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates changes in tissue protein turnover in a rat cancer cachexia model. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(6):2783–2789.

[https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI116897]

-

Cwikel JG, Behar LC, Zabora J. Psychosocial factors that affect the survival of adult cancer patients: A review of research. Journal of psychosocial oncology. 1997;15(3–4):1–34.

[https://doi.org/10.1300/J077v15n03_01]

-

Dalton SO, Schüz J, Engholm G, et al. Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003: Summary of findings. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14): 2074–2085.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.018]

-

De Leeuw JR, De Graeff A, Ros WJ, et al. Negative and positive influences of social support on depression in patients with head and neck cancer: a prospective study. Psychooncology. 2000;9(1):20–28.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<20::AID-PON425>3.0.CO;2-Y]

-

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101]

-

Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(12):1116–1127.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013]

-

Fearon KCH, Glass DJ, Guttridge DC. Cancer cachexia: mediators, signaling, and metabolic pathways. Cell Metab. 2012;16(2):153–166.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.011]

-

Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(2):90–99.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.209]

-

Flynn MG, McFarlin BK. Toll-like receptor 4: link to the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2006;34(4):176–181.

[https://doi.org/10.1249/01.jes.0000240027.22749.14]

-

Fong Y, Moldawer LL, Marano M, et al. Cachectin/TNF or IL-1 alpha induces cachexia with redistribution of body proteins. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(3 Pt 2):R659-665.

[https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.3.R659]

-

Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(3):243–251.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1571]

- Goldberg JA, Scott RN, Davidson PM, et al. Psychological morbidity in the first year after breast surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1992;18(4):327–331.

-

Grassi L, Rosti G, Albieri G, et al. Depression and abnormal illness behavior in cancer patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1989;11(6):404–411.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(89)90135-7]

-

Holsboer F, Ising M. Central CRH system in depression and anxiety--evidence from clinical studies with CRH1 receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583(2–3):350–357.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.12.032]

-

Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Depression in patients with lung cancer: prevalence and risk factors derived from quality-of-life data. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):893–903.

[https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.893]

-

Irwin MR, Miller AH. Depressive disorders and immunity: 20 years of progress and discovery. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(4):374–383.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2007.01.010]

-

Kathol RG, Mutgi A, Williams J, et al. Diagnosis of major depression in cancer patients according to four sets of criteria. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(8):1021–1024.

[https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.147.8.1021]

-

Kelsen DP, Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, et al. Pain and depression in patients with newly diagnosed pancreas cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(3):748–755.

[https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.748]

-

Kenis G, Maes M. Effects of antidepressants on the production of cytokines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(4):401–412.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145702003164]

-

Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):873–876.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00309-4]

-

Kim YK, Maes M. The role of the cytokine network in psychological stress. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2003;15(3):148–155.

[https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1601-5215.2003.00026.x]

-

Kissane DW, Clarke DM, Ikin J, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life in Australian women with early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust. 1998;169(4):192–196.

[https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140220.x]

-

Klausner JD, Makonkawkeyoon S, Akarasewi P, et al. The effect of thalidomide on the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and M. tuberculosis infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11(3):247–257.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/00042560-199603010-00005]

- Kuchler T, Henne-Bruns D, Rappat S, et al. Impact of psychotherapeutic support on gastrointestinal cancer patients undergoing surgery: survival results of a trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46(25): 322–335.

-

Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T, et al. Prevalence, predictive factors, and screening for psychologic distress in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2000;88(12):2817–2823.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12<2817::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-N]

-

Kuroda K, Nakashima J, Kanao K, et al. Interleukin 6 is associated with cachexia in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69(1):113–117.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.039]

-

Lansky SB, List MA, Herrmann CA, et al. Absence of major depressive disorder in female cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(11):1553–1560.

[https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1985.3.11.1553]

-

Lasry JC, Margolese RG, Poisson R, et al. Depression and body image following mastectomy and lumpectomy. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(6):529–534.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90010-5]

-

Laviano A, Meguid MM, Inui A, et al. Therapy insight: Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome--when all you can eat is yourself. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2(3):158–165.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/ncponc0112]

-

Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):343–351.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025]

-

Little JP, Phillips SM. Resistance exercise and nutrition to counteract muscle wasting. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009;34(5):817–828.

[https://doi.org/10.1139/H09-093]

- Lundholm K, Gelin J, Hyltander A, et al. Anti-inflammatory treatment may prolong survival in undernourished patients with metastatic solid tumors. Cancer Res. 1994;54(21):5602–5606.

-

Mantovani G, Macciò A, Mura L, et al. Serum levels of leptin and proinflammatory cytokines in patients with advanced-stage cancer at different sites. J Mol Med. 2000;78(10):554–561.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s001090000137]

- Massie, M. J., and M. K. Popkin. "Depressive disorders. en Psycho-oncology. Editor: Jimmie C. Holland.";1998.p.518-540.

-

McCorkle R, Strumpf NE, Nuamah IF, et al. A specialized home care intervention improves survival among older post-surgical cancer patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1707–1713.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03886.x]

-

McMillan DC, Leen E, Smith J, et al. Effect of extended ibuprofen administration on the acute phase protein response in colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21(5):531–534.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0748-7983(95)97157-2]

-

Mishel MH, Hostetter T, King B, et al. Predictors of psychosocial adjustment in patients newly diagnosed with gynecological cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1984;7(4):291–299.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-198408000-00003]

-

Monk JP, Phillips G, Waite R, et al. Assessment of tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade as an intervention to improve tolerability of dose-intensive chemotherapy in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(12):1852–1859.

[https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2838]

-

Musselman DL, Miller AH, Porter MR, et al. Higher than normal plasma interleukin-6 concentrations in cancer patients with depression: preliminary findings. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1252–1257.

[https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1252]

-

Newport DJ, Nemeroff CB. Assessment and treatment of depression in the cancer patient. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45(3):215–237.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00011-7]

-

Pace TWW, Hu F, Miller AH. Cytokine-effects on glucocorticoid receptor function: relevance to glucocorticoid resistance and the pathophysiology and treatment of major depression. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(1):9–19.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2006.08.009]

-

Pascoe S, Edelman S, Kidman A. Prevalence of psychological distress and use of support services by cancer patients at Sydney hospitals. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(5):785–791.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00817.x]

-

Pinder KL, Ramírez AJ, Black ME, et al. Psychiatric disorder in patients with advanced breast cancer: prevalence and associated factors. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(4):524–527.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(05)80144-3]

-

Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1797–1810.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992285]

-

Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(1):24–31.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006]

-

Raison CL, Miller AH. When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1554–1565.

[https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1554]

-

Reid J, Mills M, Cantwell M, et al. Thalidomide for managing cancer cachexia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(4):CD008664.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008664.pub2]

-

Richardson JL, Shelton DR, Krailo M, et al. The effect of compliance with treatment on survival among patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(2):356–364.

[https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1990.8.2.356]

-

Schlesinger S, Siegert S, Koch M, et al. Postdiagnosis body mass index and risk of mortality in colorectal cancer survivors: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(10):1407–1418.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0435-x]

-

Shachar SS, Deal AM, Weinberg M, et al. Skeletal Muscle Measures as Predictors of Toxicity, Hospitalization, and Survival in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer Receiving Taxane Based Chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(3):658–665.

[https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0940]

-

Skarstein J, Aass N, Fosså SD, et al. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: relation between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(1):27–34.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00080-5]

-

Soygur H, Palaoglu O, Akarsu ES, et al. Interleukin-6 levels and HPA axis activation in breast cancer patients with major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(6):1242–1247.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.05.001]

-

Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):527–533.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300039004]

-

Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):269–282.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00566-3]

-

Stefanek ME, Derogatis LP, Shaw A. Psychological distress among oncology outpatients. Prevalence and severity as measured with the Brief Symptom Inventory. Psychosomatics. 1987;28(10):530–532, 537–539.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(87)72467-0]

-

Thomas DR. Distinguishing starvation from cachexia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18(4):883–891.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0690(02)00032-0]

-

Tisdale MJ. Biology of cachexia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(23):1763–1773.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/89.23.1763]

-

Torelli GF, Meguid MM, Moldawer LL, et al. Use of recombinant human soluble TNF receptor in anorectic tumor-bearing rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(3):R850-855.

[https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.3.R850]

-

Wang H, Hai S, Liu Y, et al. Skeletal Muscle Mass as a Mortality Predictor among Nonagenarians and Centenarians: A Prospective Cohort Study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2420.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38893-0]

-

Wulsin LR, Vaillant GE, Wells VE. A systematic review of the mortality of depression. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(1):6–17.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199901000-00003]

-

Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, et al. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19–28.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::AID-PON501>3.0.CO;2-6]

-

Zaki MH, Nemeth JA, Trikha M. CNTO 328, a monoclonal antibody to IL-6, inhibits human tumor-induced cachexia in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 2004;111(4):592–595.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.20270]

-

Zhu CB, Carneiro AM, Dostmann WR, et al. p38 MAPK activation elevates serotonin transport activity via a trafficking-independent, protein phosphatase 2A-dependent process. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(16):15649–15658.

[https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M410858200]